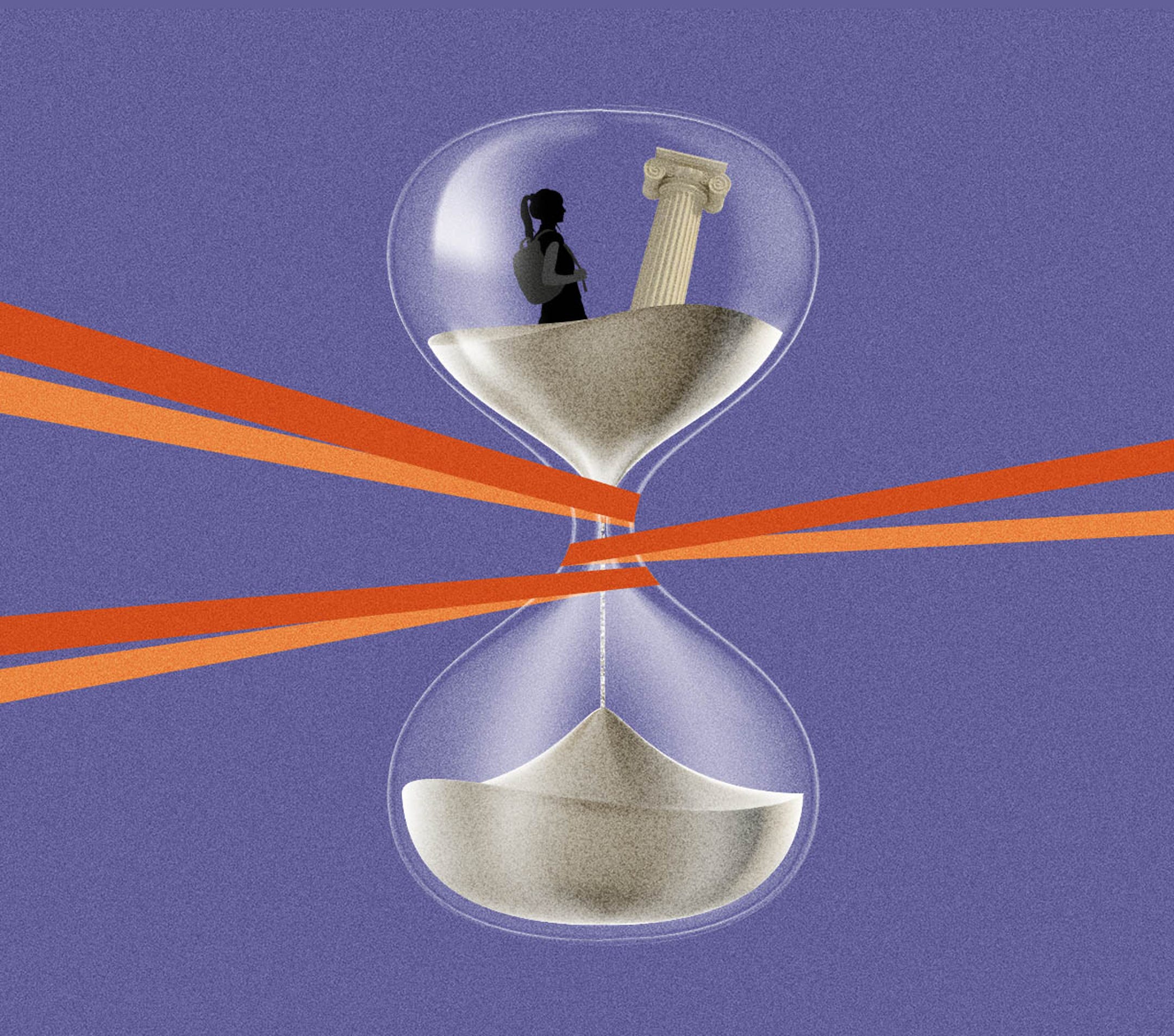

Nestled among Lexington’s rolling hills, the University of Kentucky is steeped in horse culture. Some of the best thoroughbreds in the world graze in wide-fenced paddocks outside campus. A premiere academic program draws many students to the school, which boasts eight club teams dedicated to equine sports.

Yet it does not sponsor an NCAA Division I equestrian team.

It’s not for lack of interest or demand.

Rather, the school has had overwhelming student support for adding a varsity team going back decades – and a federal investigation that should have prompted it to respond to that demand.

Instead of adding an equestrian team – or other sports that hundreds of women have shown interest in over the years – the school has pushed back.

For nine years, the university has fought against its aspiring female athletes and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, which is tasked with enforcing the landmark gender equity law, Title IX. The agency found the school out of compliance with Title IX for not offering women enough athletic opportunities. Since then, the school has questioned the way the agency interprets the law, balked at requests to add teams, denied violations, and it continues to shortchange women.

That it has done so without consequence, gender equity advocates and others say, is a symptom of a federal agency that’s ineffective at ensuring the nation’s schools comply with the 50-year-old law.

“If you want to enforce this or you aren’t enforcing it, why not,” asked Grace Bieghler, a Kentucky senior and president of one of the student-led equestrian clubs. “If the University of Kentucky has every single sport recognized by the (Southeastern Conference) except for equestrian, why not?”

The situation with Kentucky is not an outlier.

Schools accused of violating Title IX – which bans sex discrimination across all aspects of education, including athletics and sexual harassment – have little to fear from the Office for Civil Rights; they can openly defy the agency, withhold records and fail to heed agreements with impunity, a USA TODAY investigation found.

Even when the agency finds them at fault for blatant violations of the law, sanctions do not follow. Rather, it works “cooperatively” to nudge schools toward compliance with resolution agreements and monitoring – a process that often drags on for years and ends long after the aggrieved students graduate or leave school.

Its only sanction for violating Title IX is to revoke all federal funds – an act so severe that it has never used it. As a result, dozens of schools openly skirt the law, continuing to violate Title IX by shortchanging female athletes of playing opportunities and scholarships or failing to crack down on campus sexual assault, USA TODAY found as part of its yearlong investigation.

Some of its toothlessness was by design.

Congress passed Title IX in 1972 with the lofty goal of eliminating sex discrimination in schools, but it gave the Office for Civil Rights neither the alternate sanctions nor the resources and funding to efficiently enforce the law. Instead, the office is rehabilitative rather than punitive, in each case seeking to resolve discrimination amicably.

USA TODAY spent more than a year collecting and reviewing letters and agreements between the agency and universities in the NCAA’s Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, which represents many of the nation’s most recognizable and well-resourced schools. The media organization requested records covering two key areas under the law – athletics and sexual misconduct – dating back to 2011, when the agency launched a crackdown on campus sex assault. The Office for Civil Rights provided records for nearly 100 cases.

Reporters also reviewed correspondence and other documents schools provided to the agency during the course of its investigations, as well as government reports and lawsuits filed against schools for alleged Title IX violations. And they interviewed more than 40 advocates, complainants, students, attorneys, academics and current and former OCR staff.

Among the investigation’s findings:

- Even when the Office for Civil Rights finds clear evidence of Title IX violations, it rarely cites schools for non-compliance. It instead obfuscates the transgressions in bureaucratic language that stops short of assigning blame, thereby allowing schools to claim innocence while negotiating voluntary resolutions. Other times, schools opt to enter agreements before the agency renders its findings. In just 18 of the 99 cases did the agency unequivocally state that a school violated Title IX. Experts compared the process to a speed trap where violators get warnings but rarely tickets.

- The agency routinely blows past its goal of resolving cases within six months. It took an average of 26 months for it to investigate complaints and more than four years to complete compliance reviews, which are the rare cases it initiates to assess more broadly whether schools are following the law. Some compliance reviews took even longer – the one at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst took a decade. Though the Office for Civil Rights often faults schools for not reaching timely resolutions of their own, the agency fails to do so itself.

- Some schools under resolution agreements with OCR experience lax monitoring and spotty communication with the agency, which sometimes goes a year or more between contacts with schools. The University of Akron, for example, submitted proposed changes to the agency more than four years ago and has not heard from it since. At Michigan State and Virginia Tech, the agency was still monitoring agreements six years after the schools signed them.

- Schools face zero consequence for openly defying or even withholding records from the federal agency. The University of Southern California, for example, did not disclose to the Office of Civil Rights nine complaints it had received against a school gynecologist for inappropriate conduct – despite the OCR’s explicit request for all reports of sexual harassment. The agency only learned about the complaints after the Los Angeles Times published an investigation about the gynecologist, George Tyndall, who now faces dozens of criminal charges. He has pleaded not guilty.

USC did not respond to USA TODAY's question about why it failed to provide the Tyndall complaints to OCR but said in an emailed statement that it "worked in good faith to respond diligently to all of their requests and inquiries.”

Experts said those, and other issues, paint a poor picture of the enforcement landscape.

“We just know that there’s very little chance that we’re going to be held responsible for something, and even if we do it’s going to be years and years down the road so there’s just no pressure on them,” said Brett Sokolow, who works with schools as president of the Association of Title IX administrators.

The cases USA TODAY reviewed, although comprehensive, represent a snapshot of the many investigations the agency conducts under Title IX, a law that applies to all schools receiving federal funds and which covers millions of students from kindergarten through graduate school.

Because USA TODAY could review only closed cases, the analysis does not include at least 21 open cases of FBS schools currently under Title IX investigation for athletics or sexual harassment issues. Of those schools, the agency previously investigated 13 under Title IX and signed resolution agreements with nine of them.

In an interview, Catherine Lhamon, the U.S. Department of Education’s assistant secretary for civil rights under both Presidents Joe Biden and Barack Obama, defended her office’s efforts to enforce Title IX.

While the Office of Civil Rights is staffed with dedicated civil servants who believe in its mission of ensuring education free of discrimination, she said, there are too few of them to handle increasing caseloads. And while the length of time to complete investigations has expanded under her watch, that was necessary to address systemic issues, she said.

“I am frustrated that 50 years later we see so much persisting noncompliance,” Lhamon said. “It’s my goal for school communities to be clear that we will see them, we will find them, and we will correct them.”

But the agency is limited in what it sees. Because it lacks the tools and funds to proactively collect data and monitor schools for signs of noncompliance, it relies instead on aggrieved students to file complaints about potential violations. Few students understand the law well enough to recognize a violation, much less that they have a right to file a complaint.

“It’s a challenging dynamic that so many people don’t understand their rights and there’s no proactive enforcement,” said Sarah Axelson, vice president of advocacy at the nonprofit Women’s Sports Foundation, “so you’re kind of in this place where a lot of noncompliance flies under the radar.”

As a result, schools have openly violated the law or its intent for years, USA TODAY found during a broader, yearlong investigation into how universities skirt Title IX.

The media organization found that schools consistently devote fewer resources to women’s sports than men’s, manipulate rosters to appear to offer more athletic opportunities to women than they do, and deprive women of equitable scholarship funds.

When it comes to cracking down on campus sexual misconduct, USA TODAY found, universities operate in a flawed system with inconsistent enforcement and little meaningful punishment.

University of Kentucky general counsel William Thro asserted the school is in compliance and that OCR has not discussed revoking federal funds or initiated any enforcement action with the school.

“They found us in full compliance with all of the factors elucidated in the regulations,” Thro said, “except for interests and abilities.”

But meeting students’ athletic interests and abilities is key to complying with Title IX. And right now, Bieghler said, students have an interest and ability to compete in equestrian at the Division I level. It’s baffling, she said, that Kentucky won’t sponsor a team.

“It’s not OK that the Department of Education allows this to happen,” said Rep. Lori Trahan, D-Mass. “And I know that enforcement is challenging. I have no doubt that the team that’s responsible for enforcing all these provisions are overwhelmed, but if that’s the case, we need to know so we can properly resource them. Because the status quo just isn’t working for so many women athletes.”

Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., has previously introduced legislation that would give the Office of Civil Rights an alternative sanction to revoking federal funds – namely, fining schools for noncompliance. It died in committee and never made it to a vote.

It’s not unprecedented for the Department of Education to levy fines, as it has such power under the Clery Act, which requires schools to compile campus crime data and issue timely warnings. Since 2010, the department has issued Clery fines totaling more than $12 million to10 FBS schools.

“Money does talk,” said Speier. “I think that would be a way of making sure they took these cases more seriously.”

But Lhamon said she doesn’t want fining authority, believing it would “exponentially” increase the time it takes to reach resolution agreements with schools. She also said it would be difficult to determine what fines should be levied for which types of noncompliance.

In the meantime, students like Hannah Smith are left to wonder if they’ll ever see justice.

In September 2019, the OCR agreed to investigate Smith’s complaint that Michigan State failed to resolve her sexual harassment case promptly. But the agency's investigation has now lasted longer than the school's case.

Michigan State took nearly 600 days to investigate her allegations that a professor made misogynistic comments and inappropriate remarks about her appearance. The Title IX office started an investigation, outsourced it to a law firm, reassigned it to an internal investigator and then reassigned it to the original investigator. Ultimately, the school found the professor not responsible. In the meantime, Smith graduated, and the professor retired with emeritus status.

Michigan State deputy spokesman Dan Olsen declined to comment on the specifics of the case but said the university was processing an unusually high number of cases during that time. Since then, Olsen said, it has made progress to improve the timeliness of cases and is bringing in more staff to help.

"All I wanted from the Title IX office was for him to have a T.A. (teaching assistant) so he wouldn't be able to talk to me after class," Smith said. "That was literally it. And here we are, five years later."

An agency official contacted Smith a year ago to gauge her interest in settling with the school and dropping the case. Smith declined.

She has not heard from the agency since.

OCR mired in crushing caseloads, bureaucracy

Housed within the U.S. Department of Education, the overburdened Office for Civil Rights enforces six federal civil rights laws, including Title IX, that ban discrimination in education based on race, color, national origin, sex, disability and age. It does this by issuing guidance, providing technical assistance and investigating complaints.

More than 18,000 school districts and 6,000 colleges and universities fall under its purview, for which the OCR has a staff of fewer than 600 people – about half the size the agency was four decades ago despite its exploding case load amid the nation’s growing student population.

Complaints ballooned from fewer than 3,000 in 1981 – when it had nearly 1,100 employees – to a record of nearly 19,000 last year.

The agency for years has pleaded with Congress for more money to hire investigators, but lawmakers have consistently underfunded the agency’s annual budget requests, a USA TODAY review found. For fiscal year 2023, the agency is asking for a $30.3 million increase to hire an additional 101 staff members, nearly all of whom would conduct investigations. Only twice in the past 20 years has it asked for a larger increase, neither of which it got.

After reviewing the merits of each complaint, which represent the tip of the iceberg of potential Title IX violations, the OCR investigates just a fraction of those it receives each year. The agency tosses nearly 70% for timeliness or jurisdictional issues, a 2015 report from the Department of Education’s inspector general found. For example, the OCR rejects any complaint submitted more than 180 days after the discovery of the alleged discrimination.

That still leaves thousands of cases the agency opens and investigates, with staff members each juggling an average of 27 at a time. Title IX investigations often involve collecting and analyzing reams of data and records, including policies and procedures, assessments of sexual harassment cases or more than a dozen athletics categories and on-site visits and interviews.

Those cases often drag on for years, especially under Lhamon, who has directed OCR staff to look beyond the specific complaint and conduct broader, systemic probes of schools under examination.

“We have more cases, fewer investigators, and the cases are more complex at this time,” Lhamon said. “We want to move as quickly as we can, and we also are committed to taking the time necessary to separate wheat from chaff and identify where violations exist based on accurate information.”

For a complaint alleging Indiana University mishandled sexual misconduct claims, the agency reviewed 452 individual incident reports the school received. For another complaint alleging the same at Washington State University, it reviewed more than 900 reports.

For several schools, the agency consolidated investigations of multiple complaints into one case. At Washington State, three students filed complaints that the school hadn’t responded appropriately to their complaints of sexual harassment between 2012 and 2017.

The agency resolved the case in 2018 – more than six years after receiving the first complaint – finding the school had violated Title IX. As part of the resolution agreement, it required Washington State to send an email “expressing its regret” for how long it took to resolve their cases.

The case was an example of many in which former agency staffers said they were committed to enforcing civil rights law but found themselves hampered by crushing caseloads and bureaucracy.

“I never forgot that we were dealing with individual people who had suffered and been victimized,” said Amy Klosterman, an attorney at the OCR from 2007 to 2018 and one who investigated Washington State. “I feel that we did the best we could. The best that we could do wasn’t enough.”

Washington State told USA TODAY it has made efforts to improve the process for reporting concerns and resolving complaints.

Even as OCR investigations took longer, bureaucracy added to the time processing them, especially when cases involved sensitive issues, said several former staffers, including Howard Kallem, an attorney with the OCR for about 20 years before he led Title IX offices at the University of North Carolina and Duke University.

A case that took a year and a half to finish, he said, might sit on a desk for months waiting for someone from headquarters to review it because of limited staff.

“It’s sort of at some level a bit ironic because a lot of times the department is fighting schools for not timely resolving things that are super, super complicated and take time under the best of circumstances, and the department – with all the resources it has – has historically been exceptionally slow in processing reports,” said Scott Schneider, an attorney at Husch Blackwell who works with colleges and universities on Title IX cases.

“I think the Obama administration bit off more than it could chew,” Schneider added. “At some level, the process is the punishment.”

Of the cases USA TODAY reviewed, those received during the Obama administration that were closed before he left office averaged 610 days. Those opened and closed during the Trump administration averaged 387 days.

In its 2020 report to Congress and the president, the Office for Civil Rights touted its closure rate during the Trump administration, saying that it closed more than triple the number of sexual violence cases during its four fiscal years than it had closed during Obama’s last four years in office.

But that focus on closing cases came at a cost, advocates said. While it might have saved on time, it foreclosed the opportunity to make meaningful changes at many schools.

“They will tout that they closed a lot of cases,” said Adele Kimmel, a senior attorney at the nonprofit Public Justice, “but they did it at the expense of any monitoring.”

Equestrian left behind as Kentucky resists

At the end of its nearly three-year compliance review into the University of Kentucky – one that entailed multiple on-campus interviews, records analyses and an assessment of the school’s athletic program – the Office of Civil Rights found the school violated Title IX by not offering enough participation opportunities to women.

It gave Kentucky their choice on a path to compliance.

It could show that women had athletic opportunities proportional to their enrollment, which would have meant adding nearly 200 more roster spots to existing and new teams. Or it could assess female students’ athletic interests and abilities to determine whether it already was meeting their needs – and if not, it would add the sports those women wanted.

The school chose the second option and, in January 2017, signed a resolution agreement allowing the agency to monitor its progress.

Kentucky has pushed back ever since.

Despite year after year of surveys in which dozens of women say they want to participate in sports like lacrosse, beach volleyball and equestrian, Kentucky has not added any of those teams.

The school instead has argued against long-standing OCR guidance and, at times, it seems the agency has acquiesced. Its monitoring period is about to enter its seventh year as the OCR routinely extends the deadline for the school to comply. Communication between the agency and the school is spotty with gaps of several months and, in one instance, nearly two years.

In the meantime, there’s no sanction for continued noncompliance and Kentucky’s female students are still far from getting their fair share of athletics opportunities.

In many ways, the case highlights the ways the federal government’s investigations can be ineffective.

Even though it determined Kentucky violated the law, the OCR tempered its language in explaining that. Rather than state the school failed all three parts of Title IX’s “three-part test” to determine equity in participation opportunities for women, its letter of findings stopped short of such a pronouncement.

That has allowed Thro, Kentucky’s general counsel, to assert the school is complying with all three parts of the test. Although Kentucky has added opportunities for women, and cut some walk-on spots for men through roster management, female enrollment has grown at a faster pace.

A proportionality analysis of 2020-21 figures reported to the NCAA shows the school would still need to add 209 participation opportunities for women. Even counting 50 additional roster spots added for STUNT – a head-to-head cheerleading competition the school added in 2021 – Kentucky would remain among the top 20% of FBS schools with the biggest participation gaps.

“The university’s position is, we are in compliance with Title IX, the statute, the regulation and all three parts of the (three-part test),” Thro said.

The agency's vagueness also makes it harder for parents and athletes to understand what’s going on or whether they have evidence to file a lawsuit against the school, said Rep. Mikie Sherrill, D-N.J., who has been monitoring Title IX athletics issues and is working on legislation.

Students did, in fact, file a lawsuit against Kentucky in 2019 rather than wait for the OCR to force it into compliance. The case is headed toward a bench trial in February.

“When I was there, it felt like much of the time, if OCR got pushback from a school’s attorneys, they would often give,” said Brandon Carey, a former attorney in the agency’s Dallas office. “They would often step back a bit. I’m not saying not find a violation, but it’s not something that a government attorney is used to, having another attorney say we disagree with this and we’re going to fight it.”

Kentucky indeed has fought. From the beginning, the school’s attorney asserted a “categorical denial of any violation” and threatened to challenge the agency's interpretation of data and surveys. And throughout the monitoring period, that pushback has continued.

After refusing to add most teams requested by students in the surveys – arguing it must have enough Division I caliber athletes already on its campus to do so – Kentucky asserted the OCR should count the school’s existing cheer and dance teams as participation opportunities. Those are generally not considered a sport when their primary purpose is to support other teams.

When that didn’t work, Kentucky pivoted to STUNT, which the sport’s advocates say is cheap, easy and can accommodate large rosters from existing cheer teams to satisfy Title IX rules.

Though Kentucky was in touch with USA Cheer about STUNT as early as 2019, and even encouraged its consideration as an NCAA emerging sport, the school did not include it on a survey until 2021.

Months after it received results, Kentucky announced that it would add it as a sport. It’s just the third Division I team in the country and the only one in the SEC. No other conference school has STUNT at any level, but four do have Division I equestrian teams.

![Grace Bieghler, aboard Buddy, clears a jump during Equitation practice for the University of Kentucky Equestrian Team on Monday, November 8, 2022 [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://www.gannett-cdn.com/presto/2022/12/07/USAT/23ac5d84-c4cb-4ea5-a889-6fe4e5b422a4-XXX_UKequitation15_dcb.jpg)

“We kind of feel like we got left behind,” said Bieghler, the equestrian club president. “Why weren’t we in any of these conversations when we were talking about elevating a team?”

Sandy Bell, Kentucky’s executive associate athletic director and senior woman administrator, said STUNT was appealing because it’s growing quickly and finances were a consideration in adding that, as opposed to equestrian. Records from the school show the team had no official budget when it was announced and $520,000 in its first year of competition this year.

“When we used the survey results – that’s not the only thing we used – but we used the survey results and the dramatic number of young women who were both interested and able to compete in the sport of STUNT was so much larger than the others,” Bell said,

“and it fits very well into our geographical area, so that was the one we chose to add at this particular time.”

The school continues to monitor interest in equestrian, she said.

Plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Kentucky specifically sued over the school’s refusal to add field hockey, triathlon and lacrosse. But they listed equestrian among several other sports the school could add.

Jill Zwagerman, an attorney for the students in that lawsuit, said that schools know “OCR probably won’t do anything. They might come in, make our lives difficult for a while, put us on monitoring but as long as we promise to do better next time, we’ll be fine. And we know when there’s no negative consequence for them, they don’t have to change.

“It’s one of the few laws where you violate, violate, violate, violate and everyone knows you’re violating and everyone sees you violating it, but we don’t do anything about it.”

Lax monitoring, gaps in communication

Kentucky’s wasn’t the only case where the OCR extended its monitoring period or had lengthy delays in communication between the agency and the schools.

At least 19 cases in USA TODAY’s dataset were still being monitored as of September 2021 – often past the deadlines outlined in those agreements. Although the average monitoring period was three years, the agency was still overseeing changes at Michigan State and Virginia Tech six years after their cases had been ostensibly resolved.

The agency did not respond to USA TODAY’s request for updated case monitoring statuses submitted in April and November.

Lhamon said there are often reasons to extend monitoring, including when a school’s submitted data indicates additional concerns. She said the “real work in civil rights” takes place after the agreement when the agency can take the time needed to ensure the schools actually understand and comply with the law.

That’s perhaps especially true of schools that resist.

“An extension of monitoring to me is not necessarily a bad sign about OCR’s effectiveness,” said Alexandra Brodsky, a staff attorney at Public Justice who as a student in 2011 filed an OCR complaint against Yale University. “If that school is fighting compliance, then thank goodness that OCR can extend monitoring.”

Monitoring extensions aside, the agency also could pull a school’s federal funds to spur compliance. But former investigators struggled to remember the agency ever issuing letters of impending enforcement action – the administrative step that starts that process. It happened so few times that many spoke of it with a lore-like quality.

But because doing so ultimately hurts students, the agency is reluctant to do it – something many experts said schools use to their advantage.

“Certainly revocation of federal funds is a huge stick. It is an important leverage to hold for enforcement. In my experience, it was not necessary,” said Russlynn Ali, the Department of Education's assistant secretary for civil rights from 2009 to 2012. “In the cases where there were violations, the federal government should be a partner to cure them.”

Similarly, Lhamon said she has not needed to use it, though in 2014 as enforcement picked up for sexual misconduct cases, she said she raised it with several schools.

“I don’t want to withhold federal funds from school communities because ultimately that harms kids,” she said, “but I will do it if there is a school community that won’t comply with the law.”

Sometimes, however, monitoring periods drag on because of lapsed communication. After the agency found the University of Akron failed to “promptly conclude” an investigation into a student’s reported sexual assault, the school submitted proposed changes to its policies and procedures. That was in March 2018. Nearly five years later, the OCR has still not approved those. Instead, the school confirmed to USA TODAY, it has not heard from the agency.

With more pressure to resolve cases in 180 days, or at least as quickly as possible after that, former OCR investigators said active cases often could take precedence over those being monitored.

Employee turnover at the schools and the federal agency is partly to blame, as well, said OCR staff, Title IX experts and attorneys. It’s common to encounter schools with new Title IX staff who don’t realize they’re subject to a previous resolution agreement, said Sokolow, of the Association of Title IX administrators. Other times, it’s OCR staff who have left.

“I’ve had schools talk to me and say, ‘Gosh, we haven’t heard from OCR in a while. We’re starting to wonder, should we keep providing documentation?’” said W. Scott Lewis, co-founder of the Association of Title IX Administrators. “To which my answer’s always yes.”

That the cases drag on for years means those who file complaints will almost never personally benefit. For Arya Royal and other complainants who spoke to USA TODAY, doing so was more an exercise in paying it forward to future students.

When Royal was a senior at University of Virginia in January 2021, she reported her program director for sexually harassing her. The case lasted nearly four times longer than school policy prescribed. It ended in June 2022, a year after she graduated.

Virginia officials found the director responsible for sexual harassing Royal and fired him. But they overturned the sanction upon his appeal, instead suspending him for a year.

Royal knew early on that she would file an OCR complaint, she said. Virginia’s Title IX officials repeatedly failed to follow policies and communicated poorly, at times ignoring her, she said in her August 2022 complaint. The agency opened an investigation into her complaint a month later.

University of Virginia spokesperson Brian Coy said the school reviews every Title IX claim thoroughly to ensure it takes appropriate action. But some cases are more complex and take longer to adjudicate, he said, adding that the school's Title IX policy makes allowance for such cases.

This isn't the first time the University of Virginia has been under investigation. A decade earlier, the OCR launched a compliance review into the university that lasted four years, found numerous Title IX violations and resulted in a 2015 resolution agreement requiring extensive reforms.

"There needs to be a signal sent that you cannot do this, and I think OCR should be the one sending that signal," Royal said. "They need to be a lot more harsh with the people who are doing this consistently to students."

Revoking all federal funding is extreme, Royal said. But she believes fining schools for failing to comply is "exactly" what the agency should be doing.

"UVA is a lot more invested in protecting that image than making sure it doesn't repeat this," Royal said. "UVA will not care until it impacts their bottom line."

‘Congress has done nothing’

In the 50 years since it passed Title IX, Congress has done little to bolster the law or help it live up to its aspirations of addressing sex discrimination in education.

It’s not for lack of trying. Lawmakers have introduced dozens of bills and resolutions regarding Title IX in waves and largely in response to news events or societal trends. In the 1970s, they focused on athletics as administrators resisted application of the law and fretted over its effects on football.

In the 1980s, several bills attempted to address the 1984 Supreme Court ruling in the Grove City v. Bell case that said Title IX applied not to the entire institution but only to the particular program receiving federal dollars. The decision rendered the law effectively unenforceable until Congress passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act in 1988 over the veto of then-President Ronald Reagan.

In the 1990s, as female athletes and advocates for women’s sports raised awareness of continued noncompliance, some in Congress sought to compel schools to provide information on their athletic programs to the Education Department.

In the early 2000s, several resolutions voiced disagreement with changes the Department of Education under then-President George W. Bush sought to make in how schools could assess interest in athletics.

In more recent years, bills have focused on addressing sexual harassment in schools and how schools should respond.

Nearly all of those efforts died in committee.

“What’s remarkable is that in the years since 1972 when regulation under Title IX has changed so dramatically, that other than a few minor changes in the 1970s and the Grove City bill, Congress has done nothing,” said R. Shep Melnick, author of "The Transformation of Title IX: Regulating Gender Equity in Education." “It’s not surprising, I suppose, but they’ve ducked the big issues. A huge part of the problem lies there.”

Sen. Mazie Hirono, D-Hawaii, has introduced a bill five times that would require the department to establish an Office for Gender Equity to support schools in fully complying with the law through technical assistance and training for Title IX coordinators and awarding grants.

“Note that there are no Republicans on this bill,” she said. “As long as we require 60 votes to pass this kind of legislation, we’re going to face major challenges moving it forward. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to keep calling attention to the need.”

Meeting that need would better equip the overwhelmed agency to effectively enforce the law and help schools live up to the expectation of education free of sex discrimination. But 50 years on, schools continue to violate Title IX in letter or spirit and the OCR struggles to stop them.

“I do think OCR has done a lot of things that have been extremely beneficial to students, don’t get me wrong,” said Carey, the former agency investigator. “And I do believe, I strongly believe, there’s more compliance than if there was no OCR. But do I believe that OCR is extremely effective at what they do? No. I think a lot of that is probably structural.

“The main tool they have has never been used, so that’s a pretty big deal. And everybody knows they can resolve it.

Contributing: Kenny Jacoby and Chris Quintana