This article examines the structural reasons why controlling expenses – especially for salaries and facilities – has been difficult in the current economic system of major college sports. The combination of three significant economic characteristics currently drives financial choices: the non-profit organizational structure, zero-sum competition, and accelerating revenue. The combination of these structural characteristics creates inescapable upward pressure on expenses, and differentiates financial decision-making in college sports from both professional sports and other non-profit sectors. The structural uniqueness of the non-profit economic system of college sports calls for innovative business and legal solutions to curtail excessive spending and its associated problems, and ensure the long-term health of college athletics in the United States.

For-Profit Business and Non-Profit Organizations

A business exists to maximize income for its owners, while also maintaining a sense of corporate social responsibility to other stakeholders. On the other hand, a non-profit organization, such as a school or a charity, exists solely to execute its mission.

Non-profit organizations do not have owners expecting a financial return, so their leaders do not operate with the goal of making a profit. Instead, financial decisions are guided by the primary objective of mission impact, while also being mindful of long-term investments and sustainability.

Accordingly, when revenues increase for a non-profit organization, expenses tend to grow commensurately. New income is used by the organization to further pursue its mission, not to create profitable operating margins. For example, a food bank that receives a new large grant will expand to serve more disadvantaged people rather than keeping the money. The level of annual expenditures for a non-profit organization is generally determined by its anticipated annual revenues.

Athletics Departments as Non-Profit Organizations

College athletics departments and their associated foundations are structured as non-profit organizations since they are part of universities. However, they differ from most other non-profits in two important ways.

First, college athletics programs compete against each other in a zero-sum game; in other words, a college sports program can only succeed at the competitive part of its mission (win) if another fails (lose). Other kinds of non-profit organizations do not deal with this dynamic to the same extent. The zero-sum nature of competition in college sports thus creates an insatiable desire for an athletics program to make investments that drive success in the competitive part of its mission.

And second, for modern college programs in the major conferences especially, revenue has accelerated at an unusually strong rate in recent years. The median Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) athletics program experienced inflation-adjusted revenue growth of 67% from 2006-2015[1], a higher rate of revenue growth than all other non-profit sectors in the United States over this period of time[2].

The combination of zero-sum competition, revenue acceleration, and non-profit financial incentives would predict an increase in spending, which has indeed come to fruition in major college sports. With gravity-like inevitability, expenses are pulled to the threshold established by the highest revenue earners. Paradoxically, the non-profit organizational structure – typically associated with austerity and frugality – has actually helped to create the extraordinary spending growth we’ve seen.

Comparing College and Professional Sports

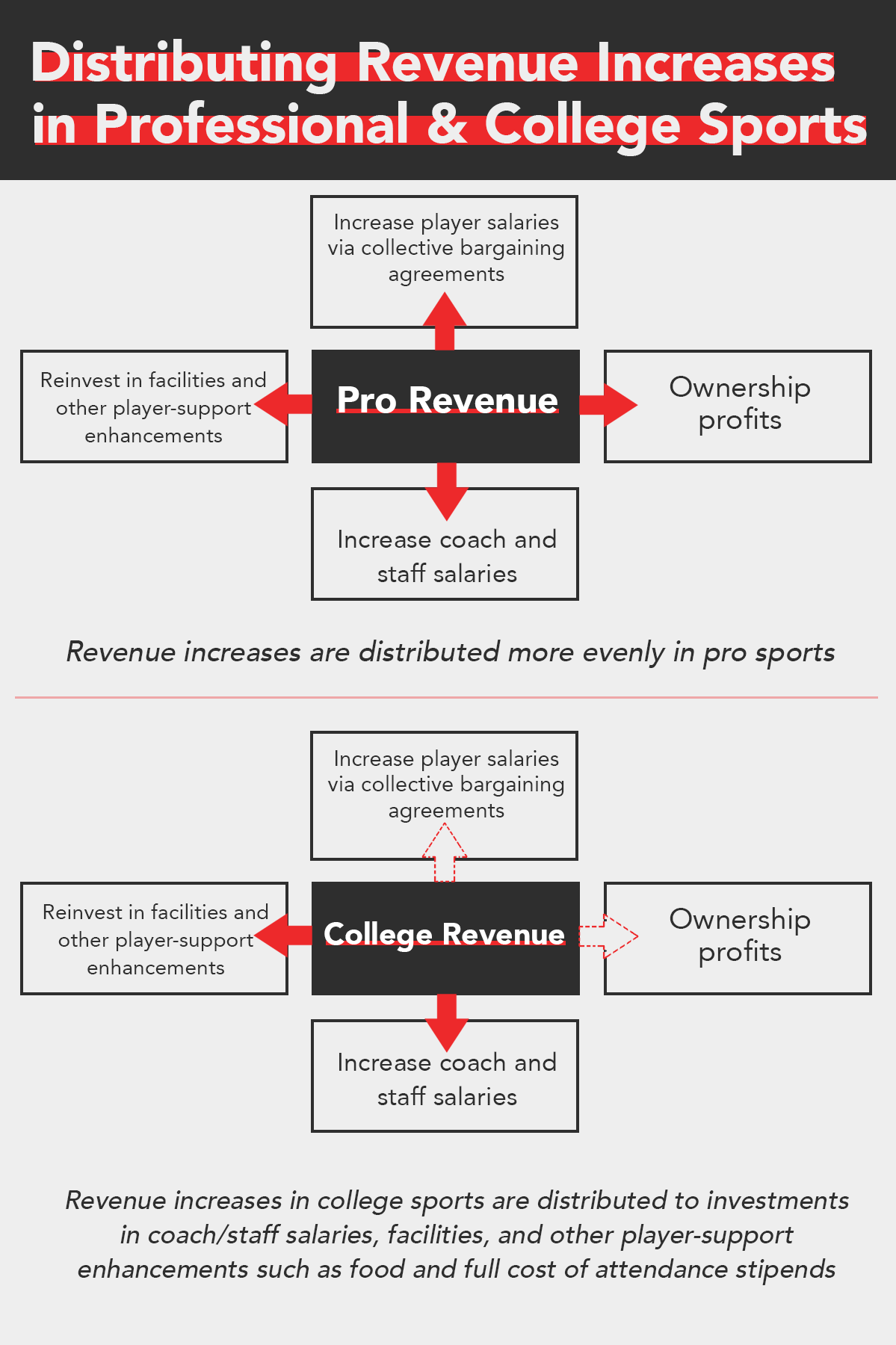

Unlike professional teams, college athletics departments do not have owners with a personal financial stake in the game. Professional owners want to win, but they are simultaneously incentivized to control costs in order to turn a profit or manage operating losses, and to consider long-term franchise value. These incentives are reflected in league-wide policies developed to control spending and enhance competitive equity, and also in the financial decision-making of team executives.

On the other hand, financial decision-making in college athletics reflects the different set of incentives that the non-profit structure encourages. Every dollar of generated revenue is spent in pursuit of the competitive and student-athlete education missions. Some income might be saved for contingent or long-term use, but none is taken as profits[3]. When revenue increases dramatically, increases in spending quickly follow.

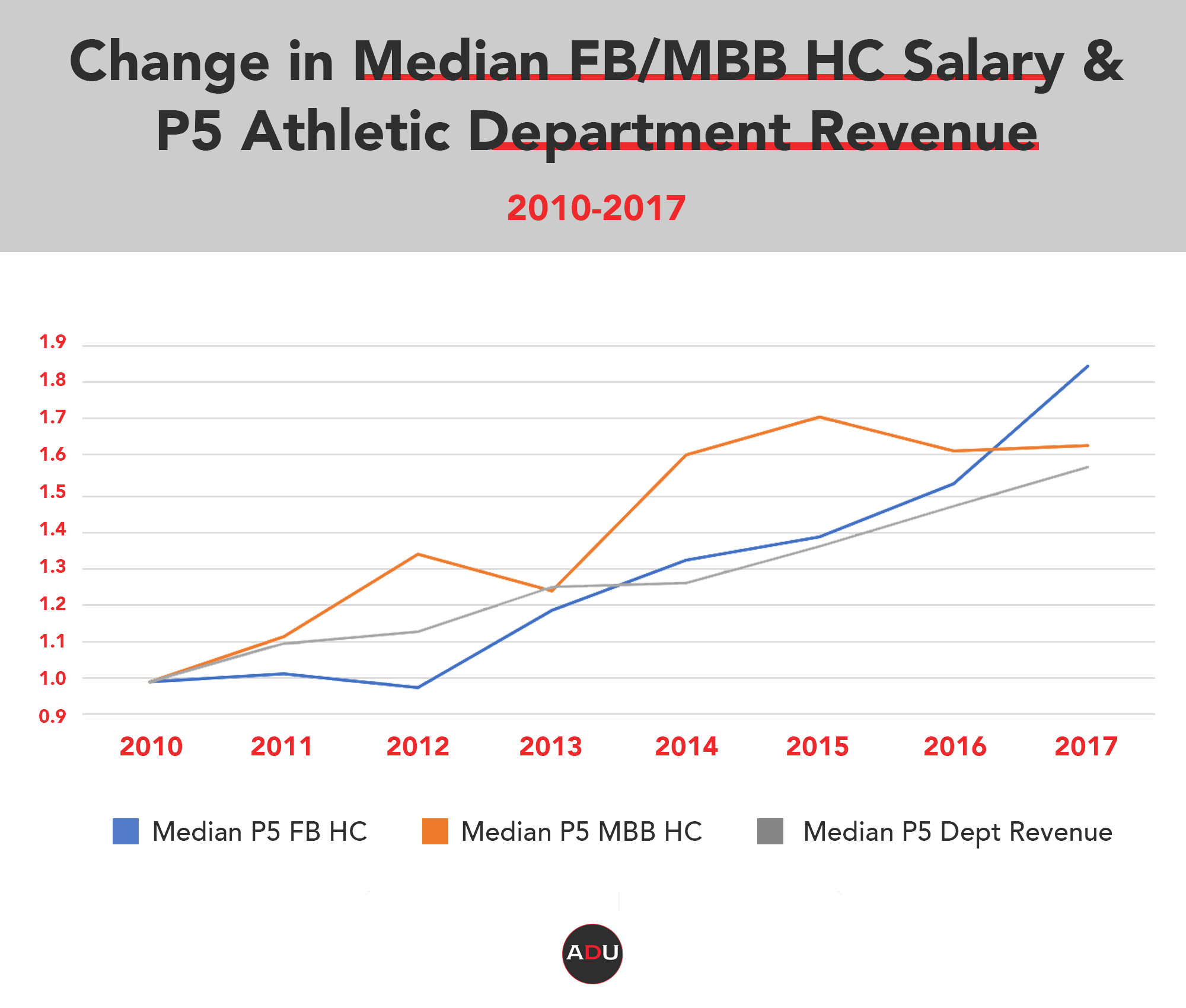

In fact, head coach salaries in Power Five college football and men’s basketball have increased more rapidly than head coach salaries in the NFL and NBA, relative to the rate of revenue growth in each environment. The median Power Five head football coach salary grew by 87% from 2010-2017, at a faster pace than the median revenue increase of 58% for Power Five athletic departments during this period[4]. On the other hand, media reports suggest that NFL head coach salaries grew by approximately 50% during the same period, at a slower pace than the 70% growth of NFL revenue. In the NBA, revenue increased by over 90% from 2010-2017, but head coaching salaries are estimated to have grown less than 40% during this period[5]. Coaching salaries grow at a faster rate in college sports than in professional sports as more revenue becomes available to fund them.

Of course, another notable difference between college and pro is that paid professional athletes share in revenue increases through collective bargaining agreements, which means that a smaller portion of revenue growth remains to flow through to coaches, management, or ownership. But the non-profit structure of athletics departments also inherently facilitates salary growth, especially when negotiating contracts with star coaches. Athletics directors and presidents do not have the support of an owner who is incentivized to keep costs in check and provide the reassurance – and personal career insurance – to walk away from unfavorable deals.

Instead, athletics directors and presidents know that they will be harshly criticized by vocal fans and influential benefactors if they fail to come to terms with a star coach, even if the terms being negotiated are not optimal for the school. Agents understand this dynamic, and have been able to negotiate college coaching contracts that are increasingly favorable as media rights revenue growth created a larger pool of available funding[6]. There is a more direct path from organizational income received to coaching salaries paid in non-profit, mission-driven college sports.

These Decisions are Rational and Predictable

From a behavioral economics perspective, financial decision-making in college sports has been perfectly rational within the structures of the current system. Aggressively reinvesting available revenue back into the competitive mission is sensible behavior that is aligned with the local interests of each school and its leadership. In some instances, there is clear evidence that a coach or team has made a transformational impact on the overall profile of a university, further justifying the decision to invest[7].

The overall increase in spending on facilities and salaries in college sports is a natural byproduct of each school’s mission-driven desire to compete in a zero-sum game, where leaders are incentivized to spend available revenue towards the competitive mission rather than make profits. Expense increases thus reflect systemic characteristics, and not “flaws” of involved individuals. College athletics decision-makers are acting rationally and predictably in the current system, just like others would if confronted with similar industry characteristics.

Why Does This Matter?

Aggressive expense growth in college athletics – that is structurally reinforced by its economic system – has created some of the most pressing challenges our industry faces. It has increased perceptions of unfairness for student-athletes and led to gerrymandering around the definition of amateurism in an effort to preserve the educational roots of college athletics. It has intensified financial pressure – ironically, given that we’re in an era of unprecedented revenue growth throughout the industry – on athletics departments who aren’t at the very top of the revenue production pyramid (i.e., the top quartile of Power Five programs) and placed these middle-income schools at an even greater competitive disadvantage. And, it has created long-term financial obligations that might turn into problematic exposures if revenue growth were to slow, stop, or reverse.

Importantly, the focal point of this issue is not the resource imbalance between Power Five schools and Group of Five or FCS, but rather the financial and competitive challenges that arise due to the effects of relative expense growth within each competitive level. For example, even though Power Five schools have more revenue to deploy than others on an absolute basis, a majority of them remain under financial pressure trying to keep up with the small group of schools who set a high bar on expenses in search of every possible competitive advantage.

Accordingly, even if setting aside financial sustainability considerations and viewing the issue only through the lens of competitive self-interest, a majority of Power Five schools ought to support a systemic solution among major conferences to control expenses. Such a system would not only mitigate challenges related to financial sustainability and public perception regarding spending, but would also enhance competitive opportunity for median schools by reducing the spending power advantage currently held by top-quartile revenue earners. In fact, successfully lobbying for a system of expense limits would be the most impactful action some schools could take to enhance their competitive self-interests.

What Should Be Done?

To stimulate progress towards a solution, a critical mass of influencers must first recognize that the expense growth problem in college sports is structural in nature – i.e., it is not the result of “flawed institutional leadership”, nor can it be effectively addressed without systemic change. The next step of identifying feasible solutions requires an in-depth legal, economic, and political analysis that is beyond the scope of this particular article.

Many people in our industry think about this problem often. Conventionally suggested methods – such as expense caps or other legislated changes about how resources are allocated or shared with central campus – are intuitive but complex to implement. Some solutions might present legal challenges, particularly around antitrust law, that could require a degree of regulatory involvement. Additionally, there would be political difficulties for some campus leaders to advocate for solutions that may be unpopular with a portion of their local constituents, a dynamic which would slow legislative progress in the member-driven governance model of the NCAA.

However, even with the complexities involved, an invigorated focus on establishing mechanisms for expense control is worthwhile, and should be acted upon as an important priority for the sustainability of college sports. Aggressive expense growth, and its associated challenges, will continue unless there is systemic change.

The economic system of major college sports uniquely combines the non-profit structure, zero-sum competition, and extraordinary revenue acceleration. It is a structural outlier in the American economic landscape, and should be managed as such from a legal and antitrust perspective. The uniqueness of its economic system calls for new thinking and innovative solutions if we seek to ensure the long-term health of college sports in the United States.

——————————————

*Undergraduate research assistants Mitch Iwahiro, Mia Motekaitis, and Tyler Mundy contributed to this article*

[1] According to the 2016 edition of Revenues and Expenses of NCAA Division I Intercollegiate Athletics Programs, median revenue growth from 2006-2015, on an inflation-adjusted basis, was 67% for FBS, 55% for FCS, and 55% for D1 without football.

[2] Information about non-profit revenue and expense growth by sector can be found on this 2018 report by the Urban Institute called The Non-Profit Sector in Brief. On an inflation-adjusted basis, overall higher education sector revenue grew by 39% from 2005 to 2015. Religious organization revenue grew by 59% over the same time period, the most growth of any non-profit sector outside of college sports.

[3] In a few cases, a portion of net income from athletics is redirected to the financial needs of main campus.

[4] Salary information gathered from USA Today database and other publicly available sources. Analysis included public school data only, unless private school coaching salary information appeared on the Form 990. Revenue data gathered from EADA reports and Knight Commission College Athletics Financial Database.

[5] NFL and NBA revenue gathered from statista.com. Salary information gathered from media reports. NFL and NBA salary information is not comprehensive, but is sufficient for the purposes of these general conclusions.

[6] Coaches are also incentivized to secure the best possible contract terms because schools are growing less patient about results. Available revenue makes it easier for schools to terminate coaches and endure switching costs.

[7] For example, here is a brief note about the major institutional impact of successful football at Clemson and Alabama.