Notre Dame AD Says NCAA Could Break Apart Without Stronger NIL Guidelines

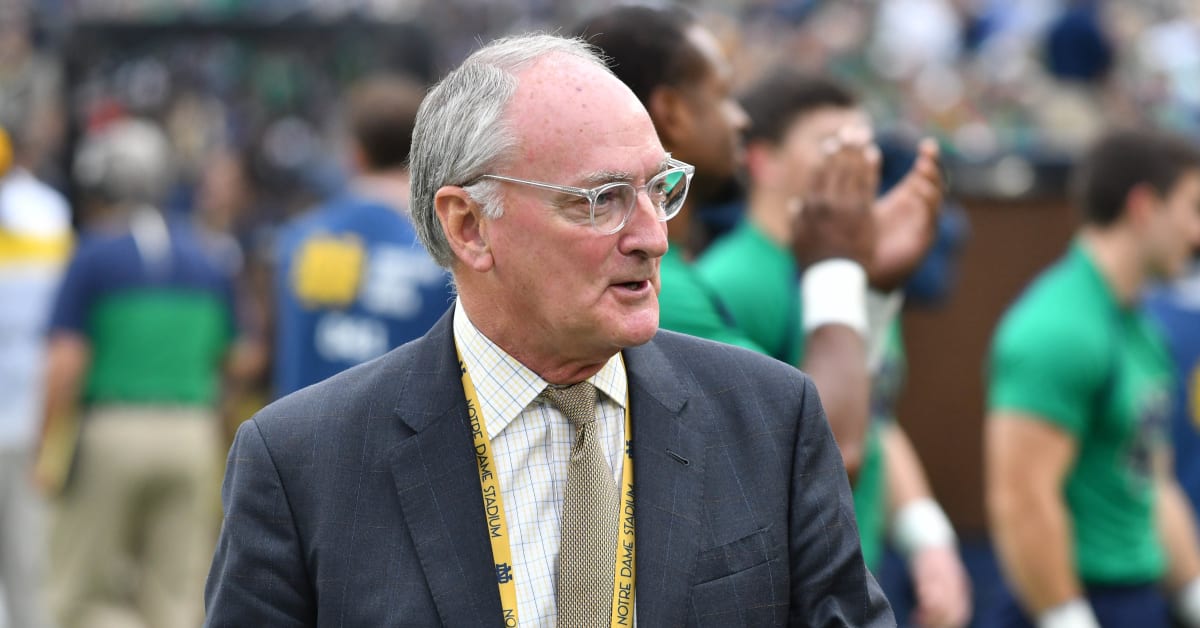

Without resolutions to name, image and likeness from itself, Congress and professional sports, the NCAA is in jeopardy of eventually breaking apart, says Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick.

In an Op-Ed in the New York Times, as well as an interview with Sports Illustrated, Swarbrick painted a stark picture of the future of college athletics if NIL continues to evolve without governance and college athletes are deemed employees—something he expects to happen in the coming months.

“College athletics is in crisis,” Swarbrick and Notre Dame president John I. Jenkins write in the Times.

Despite many of his colleagues petitioning for significant Congressional intervention, Swarbrick and Jenkins call for only “limited” federal legislation. They say Congress should rule that college athletes are not employees, preempt differing state NIL laws and allow college athletics to create NIL rules for the sake of competitive equity. They also believe the NFL should create a minor league for young players, and that the NBA should eliminate the one-and-done rule.

Swarbrick and Jenkins also write that the NCAA and its member schools should establish more stringent rules to police NIL endeavors. Without such legislation and enforcement, Swarbrick suggests to SI that the years-long splintering of the association will reach extremes, with rich, like-minded college programs breaking away.

“If we can’t start to get ourselves to where we can make rational decisions like those and enforce them, the future will be more than one athletic association. I can tell you that,” he says.

“We’ve got to get our act together as college athletics and do the things we can do. We keep sort of implying we can’t address name, image and likeness. Of course we can,” he continues. “We can do it in ways requiring reporting on transactions, requiring that there be transactions. We have to take that on as opposed to looking to others to fix it for us.”

In a view shared by many within the industry, Swarbrick expressed his intention on protecting the century-old educational mission of college athletics, which, at its highest level, is drifting toward a professional model where boosters and booster-led collectives are distributing salaries to players under the guise of NIL. The evolution of NIL has created an unregulated free agency and false market where college athletes are signing five-, six- and even seven-figure contracts to play for certain schools, administrators say.

One of the most respected in his field, Swarbrick, a former attorney, outlined a host of solutions to repair what he says is a broken system that threatens the competitive equity of college sports. That starts with the NCAA creating NIL policies—as opposed to the current “guidelines”—and enforcing those policies. Athletes should be required to report all NIL transactions to the school, he says, and it should be the school’s obligation to ensure that any transaction between an athlete/recruit and a booster is in fact a transaction in which the athlete contributes NIL value and the compensation reflects “reasonable market value.”

Among Swarbrick and Jenkins’s other suggestions in the op-ed: The NCAA should also (1) establish a national class-miss policy that limits each team’s travel schedule to avoid missing too many classes; (2) create a national medical trust fund for those injured while playing college sports; and (3) honor scholarships for athletes who wish to return to school to complete their degree.

Swarbrick tells SI these rules will not “solve the entire problem,” but are a start to regulating an unwieldy system of blatant recruiting inducements.

“People were paying under the table for as long as I've been around,” he says. “Now it’s the same payment, but they're calling it NIL. We’re not going to stop it. It’s not going to all go away. But we’ve got to get out of this position where the vast majority of the transactions occurring are not what they are being characterized as.

“Educational institutions ought to be embarrassed to be part of it. ‘We’re going to conduct a fraud here!’”

While some school collectives are dispersing millions to their athletic teams, most notably football and basketball players, other programs either don’t have deep enough donor resources or are choosing not to take part in what’s become a bidding war for talent. NIL spending is creating “division” among schools, Swarbrick says—a divide that could ultimately lead to a breakaway.

A breakaway of the Power 5 programs, or a portion of them, has been a long-discussed possibility that has gathered more momentum in this NIL era. Swelling with resources and deep donor pockets, the Big Ten and SEC have separated themselves from much of college football. A Big Ten with USC and UCLA and an SEC with Oklahoma and Texas collectively have arguably 15 of the top 20 brands in the sport, most of them towering financially over other programs in FBS.

“The next big issue is can we keep the perception of college athletics as involving all of us or does the Big Ten and SEC become college athletics in terms of popular perception, and if they do, how does that influence shape the future of college athletics?” Swarbrick asks.

In speaking with SI earlier this month, new NCAA president Charlie Baker acknowledged that the Power 5 is “a completely different business model” from the rest of the NCAA, but he believes the two can work under the same umbrella. “I think there’s a way, there’s a way to create a model that most of the work the NCAA does can support both,” he says.

Swarbrick has been “encouraged” by Baker and believes he’ll help make necessary changes within the association. Baker, a former two-term Massachusetts governor, replaces Mark Emmert, who for years led an organization that campaigned against athlete compensation. The organization fought in court to keep its amateurism model only to see it fail time and again.

“The NCAA spent so much time and wasted so much energy and money defending amateurism, which is a ridiculous proposition. Somebody has to explain to me someday why amateurism is a positive characteristic,” Swarbrick says. “No one ever said that the babysitter’s experience would be a lot better if we didn’t pay him or her.”

Baker spent a portion of his first two weeks on the job on Capitol Hill meeting with at least nine Congress members for what is expected to be the first of many trips in encouraging lawmakers that federal legislation is necessary. Of all the elements that Swarbrick and NCAA leaders are requesting, one looms above them all.

Athletes becoming employees is the “seminal issue” before college leaders, the Notre Dame AD says. There are several avenues in which athletes can be ruled employees, most notably a lawsuit out of Pennsylvania (Johnson vs. the NCAA) and through the National Labor Relations Board. The NLRB announced plans to pursue unfair labor practice charges against USC, the Pac-12 and the NCAA as single and joint employers of FBS football players and Division I men’s and women’s basketball players.

Experts say it is an ideal time for athletes to be deemed employees, given the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Alston case in 2021, the implementation of NIL, the NCAA’s restructuring and maybe most important, a Democratic-controlled White House and Senate.

“You’re going to have administrative tribunals and courts in the coming months declare student athletes in certain cases employees,” Swarbrick says. “We are most concerned about that development and its implications for our students. The students I talk to generally don’t want to be classified as employees.”

While that may be, the National College Players Association, including former NCAA athletes, are leading a movement for more compensation for athletes in light of ballooning coaching salaries and skyrocketing television contracts. More than a dozen football coaches now make at least $8 million in salary, and the Big Ten recently signed a new media rights contract worth more than $1 billion a year.

The NCPA, in fact, is backing a California bill that would require its state colleges to share revenue with athletes. The bill faces its first big test next month when it is up for a vote in the California Assembly Higher Education Committee.